This paper is published in AIDS, with a preprint on medRxiv.

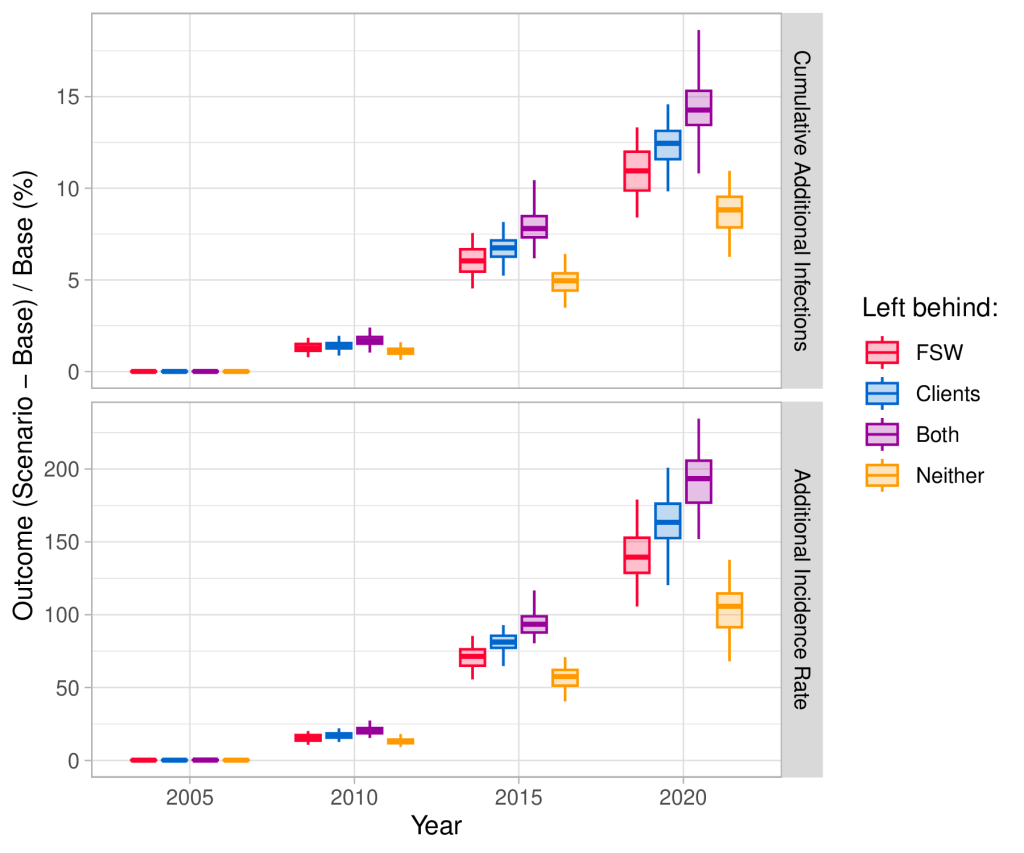

Figure 1: Changes in HIV outcomes under four “left behind” scenarios. Boxplots show the percent increase in cumulative infections (top) and additional incidence rate (bottom) compared with the base case for scenarios where ART scale-up was slower, and FSW, clients, both, or neither are left behind.

Summary

Why did we do this study?

HIV treatment (antiretroviral therapy) prevents HIV-related illness and prevents onward transmission of HIV to sexual partners. As such, massive efforts have been underway around the world to scale up coverage of HIV treatment, targeting all steps along the “treatment cascade”: testing for HIV, starting treatment, and ensuring it’s working.

Researchers have predicted that these efforts will substantially reduce the rate of new infections in various contexts. However, these predictions have almost always assumed that access to treatment was equal for everyone, even for marginalized groups like female sex workers, which is rarely true in reality. We wanted to explore the influence of this assumption on these predictions.

What did we do?

We developed a computer model of the HIV epidemic in Eswatini, a small country in Southern Africa, based on data from surveys and on-the-ground knowledge within our team. Despite a high burden of HIV, Eswatini recently scaled up HIV treatment to almost everyone in need, while minimizing inequalities in access by tailoring services to different groups.

So, we used what actually happened in Eswatini as a base case, and then simulated four “what-if” scenarios where HIV treatment scale-up was slower overall, like in other countries, and where different groups could be especially “left behind”: (a) female sex workers, (b) their clients, (c) both, or (d) neither. We then compared the rate and total numbers of new HIV infections by 2020 in “what-if” scenarios versus the base case.

What did we find?

We estimated that slower scale-up alone (d) would have led to 22,200-38,800 more HIV infections than the base case by 2020, while slower scale-up that especially left behind female sex workers and their clients (c) would have led to 39,200-62,700 more infections. We also estimated that the yearly rate of new infections in 2020 would have been twice as high as the base case in scenario (d) but three times as high in scenario (c). Outcomes for scenarios (a) and (b) were between these extremes.

In sensitivity analysis, we estimated that the impact of leaving behind female sex workers and their clients tended to increase when these groups were larger, and when HIV risk was concentrated among clients versus other men.

What do these findings mean for public health?

The expected benefits of HIV treatment will only be realized if barriers to unequal access are minimized, especially for marginalized populations already at higher risk of HIV. Unfortunately, recent cuts to global HIV funding by the Trump administration – outlined in this KFF global health policy review – threaten to do the exact opposite, reversing years of progress. By contrast, recent initiatives in Eswatini to identify and address these barriers, described in this Eswatini HIV care study, could serve as a guide and a reminder of what we can achieve.